AFI DOCS 2019: Interview with Director Jialing Zhang of “One Child Nation”

Written by: Christopher Llewellyn Reed | June 24th, 2019

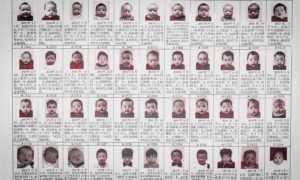

On Friday, June 21, at the 2019 AFI DOCS, I interviewed Jialing Zhang (Complicit), co-director of One Child Nation (which I saw at Sundance and later reviewed in full for Hammer to Nail). The documentary explores the devastating ramifications of China’s now-discontinued “one-child policy,” begun in the 1970s to address the country’s overpopulation crisis. Discontinued in 2015, the law, whatever its original intent, caused countless human-rights atrocities, as families either killed or abandoned extra children (often daughters). We learn that many of the Chinese babies adopted internationally over the past 30 years were taken forcibly from their parents or given up unwillingly to avoid legal problems. Zhang’s co-director, Nanfu Wang (I Am Another You), is one of the protagonists of the story, returning with her own newborn child in tow to visit her parents and relatives back in China, some of whom have disturbing tales to tell. The movie is not for the faint of heart, though gripping in its emotional intensity (and soon to be released on PBS and by Amazon). Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, with additional occasional mild rewording to make Zhang’s phrases more idiomatically American.

Christopher Llewellyn Reed: Let’s start with the fact that your film, which is really quite powerful, has some disturbing footage in it of dead babies. Will there be a trigger warning for viewers before they watch it, just to advise them of some of the content?

Jialing Zhang: Yes. We will probably put that on when we air it on PBS. When we edited the footage, it was also very hard to watch. But yes, Nanfu and I had discussions whether we should include it, but we feel that it is very necessary to include those shots because the truth was far uglier and we didn’t want to shy away from it.

CLR: And I’m not saying you should shy away from it, just that some people might find it disturbing.

JZ: Right.

CLR: So, can you take us to the beginning of your conversations with Nanfu Wang, your co-director, about making this film? At what point did you two decide to collaborate and tell this story?

JZ: So, at the very beginning, it was Nanfu. She wanted to make this story, and she reached out to me, asking if I wanted to collaborate with her. At the time, because of her previous film, Hooligan Sparrow, she wasn’t sure if she could travel back to China. She was also worried that if she traveled back, her presence there would jeopardize the film because she might attract unwanted attention from the government.

So, she asked me if I wanted to collaborate and, of course, this is a very familiar topic. Everyone in China knows a lot about it. But the more research we did, the more shocked we were because we saw so many layers of truths that we didn’t know before. The scale of all those human rights violations was very shocking to us. We decided that we need to do this story, although at that time, it was already 2016 and China had already ended the one-child policy. But we still felt there’s a sense of urgency.

CLR: And beyond what we might think we know of the one-child policy, there’s also the way it ties into international adoptions, which is an additional disturbing layer.

JZ: Right, yeah.

CLR: So, it’s primarily Nanfu’s story, as told. How did you divide the labor as two directors? Obviously, she’s in front of the camera quite frequently, but you’re both directors. So how did that work?

JZ: At the beginning, I made more of the research trips to China, and then later, after we decided to include her story in our film – because she wasn’t quite sure whether to include her story in the film at the beginning because her previous two film were all first-person perspective, and she wasn’t sure she wanted to do it again – after maybe a year, she traveled back to China. That was the first time she traveled back to China after Hooligan Sparrow, and nobody from the government showed up to question her. So, she decided to make more trips back to China.

Then, we decided not to travel together to China because the two of us together would get a lot of attention. So, whenever she traveled to China, I just monitored her on a GPS tracker, and then made sure she is at the right location at the right time. If she stayed too long in a certain location, I just had to be very alert. We made a lot of emergency plans, in case she went missing for a few hours or few days, of what we should do. Then, I would bring the whole team aboard.We stayed in touch. She’d bring the footage back to the U.S. and we edited it together. And for all the U.S. trips, we traveled together.

CLR: So, does that mean you controlled the crew? She was traveling on her own and then you’d come find her with the crew?

JZ: She also controlled the crew. We both made decisions together, but there are a lot of things I couldn’t do, not being around, so I just prepared everything very cautiously, to make sure she was safe and we were able to get a story done.

CLR: Beyond the worries of Nanfu and the risks she was taking, there are a lot of people in the film telling stories that are not very flattering to the one-child policy and reveal some really disturbing secrets. Did you have any concerns about the risks that these other people were taking, and did they have concerns about appearing on camera?

JZ: Yes, but I see the risks as lying more with the filmmakers than for the interviewees, based on experience. I think they might get questioned by the government, but they can get away. But the filmmakers, because the film is more like a statement, the risk is greater for us. Again that’s based on previous experience.

CLR: So, do you think this being released now will create further problems for Nanfu, and possibly for you, traveling back and forth?

JZ: Yes, it’s very likely. Although now, nothing has happened yet, but I think our film is already … because in China we have a version of IMDb, called Douban, a Chinese version … and our film already had a page for a few days, which then got deleted. Then, they had this complete list of 2019 winners from the Sundance Film Festival, and every other film is there, but not One Child Nation. So, certainly someone is paying attention, but we don’t know yet.

CLR: Right. So, I’m curious about that Utah family that runs Research China. Since I’ve seen Nanfu’s film I Am Another You, I’m curious if she met them while making it, since there she goes to Utah with her subject. Or was it just from research for this film?

JZ: That’s from research, but it’s such a coincidence, and she was happy to travel back, too.

CLR: Yeah. That’s quite a remarkable film, I Am Another You.

JZ: Yeah, yeah.

CLR: I’m not familiar with your work prior to this. Can you describe that work and how it fits into this particular documentary? Is there a similar topic?

JZ: This is my second feature film. My first feature film, also a documentary, is called Complicit. It’s about workers working for electronics factories in China who got poisoned by toxic chemicals. That film is similar only because they’re both about human rights. In that film, we followed people who got leukemia. They suffer from leukemia, but become activists and fight against global brands.

CLR: Got it. Could you please describe your own personal trajectory, then? Like Nanfu, you came to the United States to study film?

JZ: I went to college in China, and then I worked for a foreign-media office in Beijing for several years. I came from a strong journalism background before I went to study documentary filmmaking at NYU. It’s the same program that Nanfu went to, and the journalism school has a Master’s program. After that, I traveled back and forth doing a lot of freelance work for documentary projects for Vice, on HBO, The New York Timesand also Fusion TV.

CLR: So, I also went to NYU, but to Tisch, for their MFA program. I noticed that the film lists Carol Dysinger, one of my former professors, as one of the editorial advisors. How did you meet up with her?

JZ: She’s Nanfu’s friend, and I think Nanfu was her student, too. She took her class when she was at NYU. I didn’t, but she’s great. She’s very sensitive, and she also offered a lot of help with the structure and made us think deeper about the film. She’s a great consultant.

CLR: She’s a really great producer and editor, so I’m not surprised that she was helpful. So, how did you negotiate access to some of your subjects? Were there any people that you really had to work hard to get in the film, and any people who just refused to be a part of the film?

JZ: We got refused by many, many people. For each interview, we had to maybe try five or six failures before we would get one to agree. For Nanfu’s side of the story, some people from her family had obviously known from when she was a kid. For the twin whose sister was adopted, when we interviewed her, she hadn’t found her sister yet, so she was hoping to find her through the film.Also for the family planning officials, we had a list of over 20 people. For the main one, we got refused several times and then finally she agreed.

For the human trafficker, I think he wanted to talk to us because he is labeled by the government as a human trafficker. He felt that he got wronged because he got paid by putting abandoned babies into the orphanage. The court didn’t find any evidence of kidnapping, abducting, and still he’s labeled as a human trafficker. The family spent all those years in jail, while almost all the orphanage people, employees, etc., got away. Only one director got sentenced for one year, but he spent three three months in jail, and then he continued to work for the government and got promoted. So that man – the trafficker – he just wanted to tell his story.

CLR: Yes, there does seem to be some arbitrary application of the rules, as in any bureaucracy, where some people get away with things and some people don’t. I don’t think that’s unique to China, but it was an interesting aspect of the film.

JZ: Right.

CLR: Well, it’s a really powerful film and I want to thank you so much for making it.

JZ: Thank you!